Your Older Brother is Following You on Social Media: Will Georgia Introduce Internet Censorship

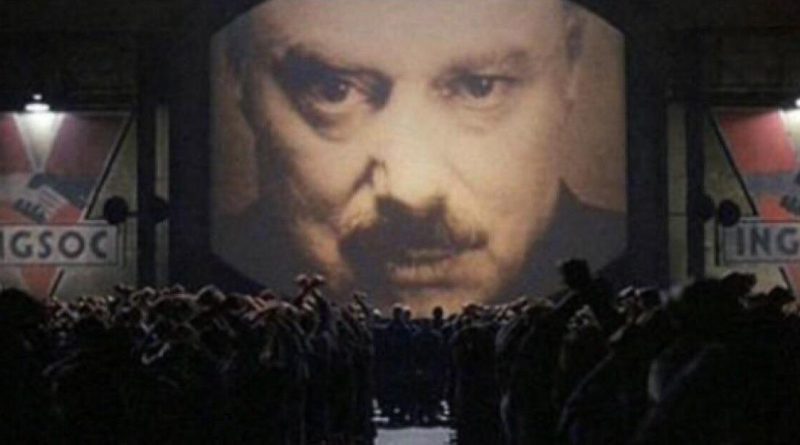

Amid a wave of repressive laws, Georgian parliament has moved to surveilling social media. Former member of Georgian Dream and current leader of the satellite party People’s Power, Sozar Subari, has advocated for the control of online posts. It’s supposedly necessary to protect privacy and prevent insults to authorities. Experts, though, say there are already a number of laws in the country limiting statements on social media, and the amendments could bring total censorship.

Translated by Adrian Bader

“Social media today has a larger influence on public opinion than television or news. It would be good to start regulating this space in order to protect dignity and privacy and prevent abuse.”

Sozar Subari, the former journalist, Free Radio correspondent, and Kavkasioni newspaper editor, stated. From 2000 to 2004, he was associated with human rights NGO Freedom Institute and from 2005 to 2009 served as Georgia’s ombudsman, actively criticizing authorities for violating human rights.

Today Sozar Subari is the reverse, fighting to create more and more restrictions for civil society. In particular, he is introducing a law limiting not only the media but individuals on the internet.

Laws imposing penalties for posts on social media exist in many countries. However, depending on the political stance of the government, these laws vary in severity and how they are applied.

Currently, Georgian parliament is already reviewing new laws potentially limiting freedom of speech and civil rights. Deputies passed the Georgian equivalent of America’s FARA (Foreign Agents Registration Act) in the first reading and are amending a law on broadcasting. Although the ruling party is justifying it as a Western practice, according to human rights activists, both laws possess repressive elements.

Georgian Dream denies accusations that they are attempting to establish censorship, lying each time about the necessity for installing regulations. Speaker of Parliament Shalva Papuashvili has repeatedly said that media and social platforms are used to “spread hostile anti-government propaganda” that threatens national safety. In January 2025, Papuashvili even declared Facebook had biased fact-checking, and a month later erupted in threats against Publika publications for announcing a protest.

“Given the latest legislative trends as well as the controversial Transparency of Foreign Influence law, this [control of social media] needs to be taken seriously,” warned Andro Gotsiridze, a cyberstrategy consultant and founder of the CYSEC research center.

According to Gotsiridze, there still isn’t a specific law limiting freedom of speech online, but existing laws partly concern it. For example, the Protection of Family Values and Minors law adopted in 2024, which prohibits LGBT propaganda in media, education, and the public sphere. This includes censoring of films, books, and public activities distributed on social media, which can be restricted due to LGBT related topics.

There is also Georgia’s Commission on Communications, whose powers are becoming even blurrier with the amendments to the Broadcasting law. But according to an Institute for Development of Free Information (IDFI) report, even without expansive laws regulating media, the commission still blocked 480 sites in 2023, mostly for copyright violations.

Specialists are afraid that Subari’s application might have a repressive element that brings full censorship online. Authoritarian states, such as China, Russia, and Turkey, have some overlap with Georgia regarding methods of controlling free speech; there exist strict laws which impose jail time for posts that criticize the government or spread fake news. For example, in China, posts found to be encouraging riots can result in up to seven days in jail.

“There exists a real risk if Georgia continues on a path strengthening control over media. In Russia, laws on fake news and disrespect of the government are used to suppress dissent and opposing voices. If Georgia brings similar measures, there can be a serious effect for freedom of speech and democratic discourse,” Gotsiridze says.

As the expert notes, Russia’s interest in controlling social media became especially clear in 2012 after the “Arab Spring” when a “blacklist” law was passed for the internet, allowing sites with unwanted content such as child pornography or suicide pleas to be blocked. Later, it was expanded to include “extremist” content.

In 2014, a law on bloggers came into effect, ordering popular platforms to register as media, subjecting them to strict laws. In 2017, access to VPNs and methods of evading censorship were blocked, and in 2019, a law was passed on “sovereign internet” requiring hardware to be installed to analyze internet traffic. In 2020, fines were added for platforms failing to delete prohibited content and those removing Russian media.

After the start of the war in Ukraine in February 2022, measures were tightened. Already by March, a law was passed criminalizing the spread of “false information” about the Russian army, punishable by up to 15 years in prison. Among those accused were Andrei Bubeev, a blogger from Tveri, who received a year in jail for reposting an article about the war in Ukraine, and Artyom Kamardin, a poet from Moscow, who was charged with seven years for poems criticizing the war.

Based on the latest OVD-Info and Freedom House reports, around 500 people in Russia are in prison or under investigation for social media posts criticizing military activity. In March 2024, 287 people were already in prison for such posts, and a year later, in March 2025, the number had increased to 300-400 people with reports of new cases.

“This is technically feasible [in Georgia], but it would require significant investment in recording technology and human resources. Countries like Russia, Iran, and China, have established extensive monitoring systems that use an artificial intelligence run surveillance system, legal obligations for the platform to share data, and direct censorship tools. However, implementing such systems in Georgia will be met with resistance by civil society and the international community,” noted Gotsiridze.

According to the cybersecurity expert, such steps contradict Georgia’s western aspirations, and their adoption brings the country closer to authoritarian models like Russia, Iran, and China, “rather than the democratic principles that our Western partners uphold.”